Ziqun Jia, Climate Finance Analyst at Perspectives Climate Research

Max Schmidt, Research Associate at Perspectives Climate Research

Igor Shishlov, Head of Climate Finance at Perspectives Climate Research, Executive Director of the Climate & Business Program at HEC Paris

1. Introduction

Export credit agencies (ECAs) are little-known public finance institutions (PFIs) that are pivotal for enabling investments in energy infrastructure worldwide. Historically, their support has mainly focused on investments in fossil fuels although it is slowly shifting towards clean energy. In 2020-2022, ECAs of the world’s biggest economies (G20) alone provided an annual average of USD 32 billion in public finance to fossil fuels (O’Manique et al., 2024), down from USD 40 billion in 2018-2020 (DeAngelis and Tucker, 2021). At the same time, they provided USD 5 billion annually to clean energy in 2020-2022, up from USD 3.5 billion in 2018-2020 (O’Manique et al., 2024). Therefore, there is still a large potential for shifting official export finance from fossil fuels to clean and renewable energy (RE), which would have a major impact on the energy transition thanks to ECAs’ ability to leverage additional finance.

ECAs are either private companies that act on behalf of a government or public entities themselves (OECD, 2021). Their purpose is to provide trade financing and risk mitigation products to support domestic companies in their international export activities and improve their competitiveness abroad. ECAs may be either pure cover – i.e., only providing insurance and guarantees – or multi-purpose – i.e., also providing direct financing (Shishlov et al., 2021). ECAs typically support larger and riskier projects that would not have been insured otherwise – historically fossil fuel infrastructure and more recently RE – which underlines their relevance for achieving energy transition and climate targets. Recently, ECAs have also increasingly taken a more proactive role as trade facilitators in addition to being insurers or lenders of last resort (e.g., Klasen et al., 2024).

Keeping global warming to 1.5°C will require significant and reliable finance to enable the rapid development and deployment of clean energy technologies. However, structural constraints exist for financing clean energy, including higher upfront costs, sensitivity to interest rates, currency risks and lack of de-risking measures, to name only a few (King et al., 2023; Schmidt et al., 2024). These and other factors make it challenging for private actors to accurately price and manage risks associated with climate investments (Hale et al., 2021). In this light, ECAs may be well-positioned to address these risks and support the accelerated deployment of clean energy globally.

2. Global Trends in ECAs’ Clean Energy Financing

2.1. Historical support to fossil fuels

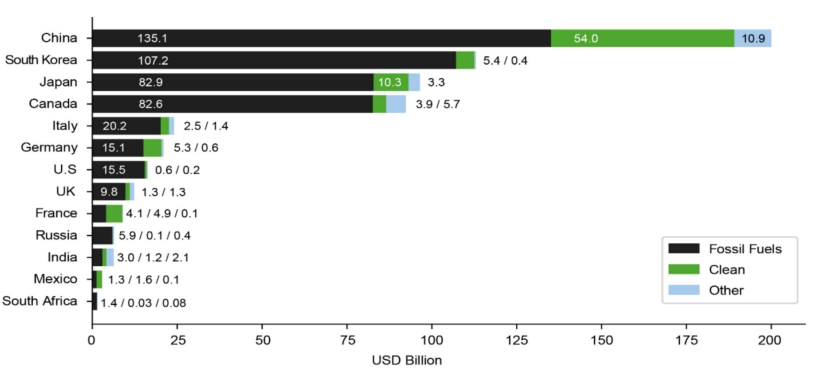

Historically, ECAs of G20 countries have allocated a staggering USD 534.4 billion to fossil fuel-related projects between 2013 and 2022, accounting for 76% of all their energy finance. Specifically, gas-related projects accounted for 28%, mixed oil and gas (O&G) followed with 24%, with oil and coal projects taking up 15% and 9% respectively. Clean energy, in turn, merely made up 10% of all energy finance in the same period, with USD 69.37 billion invested in solar, wind, tidal, geothermal, hydro, biomass, and nuclear (OCI 2024). By country, China, South Korea and Canada have had the largest absolute ECA support for energy finance, with fossil fuels taking up more than 60% of their energy portfolios (see Figure 1). Within the G20, the ECAs of France (>1/2) and China (~1/3) together with Germany’s (~1/4) showed the largest relative shares of clean energy. The energy portfolio of most other countries’ ECAs remained fossil fuel dominated.

In recent years, ECAs have increasingly contributed to clean energy finance (e.g., Klasen et al., 2024), especially for emerging markets and developing economies (EMDE). During 2020-2022, ECAs provided an annual average of nearly USD 5.2 billion for clean energy, up from only USD 3.5 billion between 2017-2019 (OCI, 2024). However, the shift from fossil fuel to support for RE is not nearly as fast as needed. Klasen et al. (2022), for example, find minimum needs for climate-related ECA commitments, including for clean energy projects, of USD 51.3 billion per year until 2030 – ten times more than the current level.

Figure 1: G20 countries with the largest ECA energy finance (2013-2022)

Source: Authors, based on (OCI, 2024)

Note: To provide more accurate representation of China’s involvement in overseas energy finance, the authors reclassified CDB from Development Finance Institution (DFI) category to the ECA category, which makes the graph different from OCI’s website. Indeed, while CDB and CEXIM are officially classified as policy banks, they also function as major export finance institutions, since they provide extensive financing support for Chinese companies' overseas activities, including export credits, buyer's credits, and project financing for those abroad.

2.2. Increasing support to clean energy

Yet, the turning trend becomes gradually notable. In H1 2023, global ECA support to RE reached a record high of USD 11.7 billion, almost four times higher as in H1 2022 with USD 3 billion (TXF, 2023). This was aided by climate-related measures and strategies agreed on and passed by several ECAs in recent years, besides improving transparency of financial and non-financial reporting (Schmidt et al., 2024c). For example, the OECD negotiations in 2023 successfully broadened the possibilities of using financing for green and climate-positive projects, to modernize export credit rules and better support the energy transition (European Commission, 2023). Some ECAs go even further: The ECA of Finland – who chaired the OECD negotiations in 2023 – allows the maximum export credit amount to be higher (up to EUR 40 million) if preconditions are met according to international frameworks such as the EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities (Schmidt et al., 2024a). Outside the OECD, China’s SINOSURE integrated the EU–China Common Ground Taxonomy into its business information systems for identifying relevant projects and customers (Chen and Shen, 2022; SINOSURE, 2023).

Over the past few years, there has been growing recognition of ECAs' potential to provide clean energy finance, marked by several noteworthy commitments targeting export finance made by governments and ECAs. For example, the ‘Export Finance for Future (E3F)’ initiative was launched in 2021, aiming to promote and support investment patterns shift towards climate-beneficial export projects (E3F, 2022, 2023, 2024). Later that year, at the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26), the Statement on International Public Support for the Clean Energy Transition (CETP) was launched. In 2022, signatories of CETP (governments and PFIs) reduced their fossil fuel financing by USD 6.5 billion, while supporting clean energy with an additional USD 5.2 billion (Jones and Mun, 2023). The same year, the Berne Union – the largest association for the export credit and investment insurance industry worldwide, of which China’s SINOSURE is a member – launched its Climate Working Group (CWG) to advance “thought leadership and practices within export credit […] and contribute to global problem-solving around climate challenges” (Berne Union, n.d.). At COP28, the UN-convened Net-Zero Export Credit Agencies Alliance (NZECA) was launched, the first-of-its-kind net-zero finance alliance of global PFIs, including associate members outside the OECD (Kazakhstan and the UAE). Most recently, at COP29 NZECA published its Target-Setting Protocol, a dedicated tool for all ECAs to accelerate their net-zero journeys and allow for a high degree of comparability (UNEP-FI 2024).

So far, ECAs of three countries – Denmark, Finland and Sweden – are already aligned with the Paris Agreement, as found by independent assessments of the authors (Perspectives Climate Research, 2024). Notably, these ECAs have achieved 100% of all energy-related transactions for RE and related infrastructure in parallel to putting in place strict fossil fuel exclusions (Schmidt et al., 2024a; Schmidt et al., 2024b; Weber et al., 2024). Admittedly, few other countries have comparable structural advantages as Denmark with its favorable wind conditions and ECA-backed global wind power manufacturers (Ørsted and Vestas Wind Systems). That said, globally ECAs start at different stages in their journey of transitioning away from fossil fuels and towards clean energy (Weber et al., 2024). China as a recognized leader in clean technology is therefore well-positioned to significantly contribute to the shift of the global export finance landscape towards clean energy.

3. China’s ECAs in clean energy finance

3.1. China’s evolving role in the global energy finance

As the world's largest provider of public finance for overseas energy projects (Chen and Liu, 2023), China can wield great influence in supporting the energy transition in the Global South, via the China Development Bank (CDB), Export-Import Bank of China (CEXIM) and China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation (SINOSURE). Historically, China has been the largest coal producer and public financier for overseas coal power plants, accounting for 50% of global public coal finance between 2013 and 2018 (Ma and Gallagher, 2021). However, its financial support for overseas coal investments peaked in 2019 with USD 4.8 billion and declined significantly in the following year (OCI, 2024). With the announcement to stop building new coal-fired power projects abroad in 2021, China has now fully phased out support to overseas coal power plants, and has become the global powerhouse for RE technology exports (Christophers, 2024). The latter is mainly attributed to the ‘New Three’ exports – solar photovoltaic (PV), lithium-ion batteries and electric vehicles (EVs). In 2023, China alone produced 86%, 74%, and 68% of all solar modules, lithium batteries, and EVs respectively, totaling over USD 150 billion in value (Song et al., 2024; Zhang and Nedopil, 2024).

The country's rapid advancements have not only shaped its domestic energy landscape, but also positioned it as a key exporter of clean energy solutions to the world (Zhang and Nedopil, 2024). This dual role as both a major public financier and clean technology provider places China and its ECAs at the forefront of “transitioning away from fossil fuels”, as agreed at COP28 in Dubai (UNFCCC, 2023).

3.2. China’s export finance landscape

From the 1990s, China began to set up its export finance institutions: CDB, CEXIM and SINOSURE. They work in close coordination but each serving distinct purposes and complementing one another to bolster international trade and investment. They are crucial in facilitating Chinese enterprises' entry into global markets, enhancing the competitiveness of Chinese products, and supporting national strategies like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that seeks to build infrastructure and trade networks across Asia, Europe, Africa, and beyond (CEXIM n.d.). Together, the three institutions have become the largest public financiers for energy-related projects worldwide, with nearly USD 200 billion between 2013 and 2021 (OCI, 2024).

Table 1: Overview of CDB, CEXIM and SINOSURE

Key aspects |

CDB |

CEXIM |

SINOSURE |

Type |

Development finance institution |

Policy bank |

Export credit agency |

Mandate |

Support China's economic development in key industries and underdeveloped sectors |

Support foreign trade, investment, and international economic cooperation |

Promote foreign trade, cross-border investments and economic cooperation through export credit insurance and investment insurance |

Main instruments of financial support |

Long-term non-concessional loans, project financing, overseas investment, equity investments |

Preferential loans for Chinese companies operating abroad, preferential export buyers’ credits, international guarantees, loans for overseas investment, concessional loans for foreign aid projects |

Export buyer’s credit, insurance, guarantee, overseas investment, project financing |

Total assets as of 2023 |

USD 18.65 trillion |

USD 6.38 trillion |

USD 197.58 billion |

Volume and share of export finance in commitments outstanding (2013-2021) |

USD 230 billion (8.7%) |

USD 278.64 billion (32.4%) |

USD 854.75 billion (92%) |

Source: Rudyak, 2020; CDB, 2024b, n.d.; CEXIM, 2024, n.d.b; SINOSURE, 2024a, n.d.

Note: CDB does not disclose the breakdown of domestic versus overseas commitments as shown in the last row. Thus, figures from OCI’s Public Finance for Energy Database have been chosen as the best available proxy.

China Development Bank (CDB) is a state-owned and policy-oriented development finance institution, dedicated to supporting China's economic development in key industries and underdeveloped sectors (Rudyak, 2020). It is China’s major development bank domestically and the world’s largest national development bank with total assets of USD 2.63 trillion in 2023 (CDB, 2024b). CDB provides extensive financial products including long-term non-concessional loans, project financing, overseas investment, and equity investments (CDB, n.d.). Despite a dominant share of domestic business, CDB also provides large overseas lending, amounting to a total of USD 230 billion between 2013 and 2021, with energy-related finance taking around USD 99 billion (Chen, 2020; AidData, 2023; OCI, 2024)

Export-Import Bank of China (CEXIM) is a state-owned policy bank that supports China’s foreign trade, investment, and international economic cooperation. CEXIM receives the same credit ratings as China (CEXIM, n.d.b) and can thus cover up to 85% of a project’s overall costs through export credits (Rudyak, 2020). It provides a range of services including not profit-oriented export sellers credits, i.e., preferential loans for Chinese companies operating abroad, preferential export buyers’ credits, international guarantees, loans for overseas investment, and concessional loans for foreign aid projects (e.g. CEXIM, n.d.a). During 2013 and 2021, CEXIM has provided USD 211 billion for overseas energy projects, and by 2023, the export-related commitments outstanding reached USD 278.64 billion (CEXIM, 2024)

China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation (SINOSURE) was created in 2001 by merging the export credit insurance departments of CEXIM and the People’s Insurance Company of China (CCPITGS, 2013). Since then, SINOSURE has been China’s official export credit and insurance agency. By implementing state decisions and plans, SINOSURE plays a crucial role in stabilizing foreign trade and bolstering the economy (SINOSURE, 2024a). By safeguarding non-payment risks, SINOSURE enhances the confidence of Chinese exporters and financial institutions, thereby strengthening their capacity to conduct overseas investment initiatives (SINOSURE, n.d.).

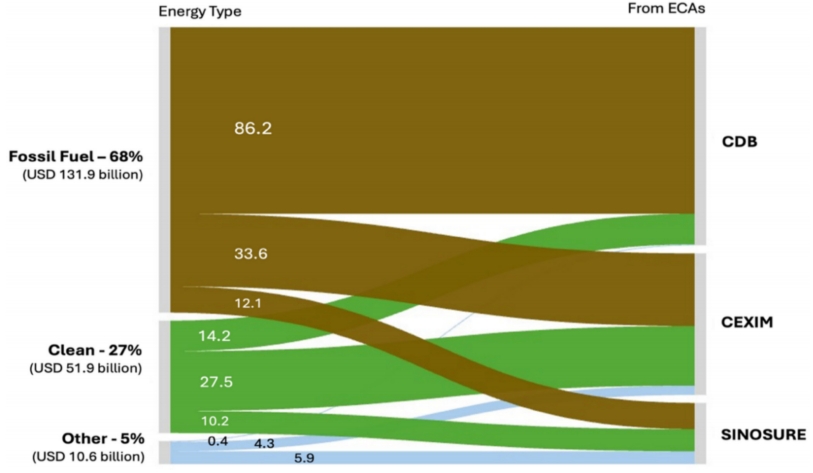

3.3. Financing portfolio of China’s ECAs

During 2013-2021, around USD 132 billion or 68% of the energy finance from Chinese export finance institutions was directed towards fossil fuel projects (see Figure 2). For those, CDB contributed the largest share (USD 86.2 billion), double that of second-ranked CEXIM. In contrast, clean energy only accounted for 27% of the total, with CEXIM leading with USD 27.5 billion, while CDB and SINOSURE contributed USD 14.2 billion and USD 10.2 billion respectively. Additionally, 5% of the finance was categorized under 'Other' energy types, including uncleared or unidentified energy projects.

Figure 2: Chinese ECAs’ energy finance by sector (2013-2021)

Source: Authors, based on OCI (2024)

These numbers indicate the dominance of fossil fuels and a relatively minor diversification in energy investments among Chinese export finance institutions in the past decade. During this period, the three ECAs showed fluctuations in funding clean energy projects by volume, while the share of clean energy increased only gradually, suggesting that a significant transition towards Paris-aligned finance has yet to come (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Chinese ECAs' energy finance by years (2013-2023)

Source: Authors, based on OCI (2024)

Notably, while investing heavily in coal before, all these institutions successfully stopped financing new coal power plants after Xi Jinping’s pledge in 2021. Further, no new public energy finance was provided to EMDEs and Global South countries by China in 2022 (Springer et al., 2023), neither for fossils nor RE, marking a strategic transition period for Chinese public financiers. Then, according to the Chinese Loans to Africa Database, the country’s energy financing returned to Africa in 2023 after a pause of two years, with a total of USD 502 million investing in three RE projects (solar and hydro), all financed by CEXIM (Engel et al., 2024). Although the absolute volume of clean energy finance is yet to witness a strong increase, this RE-focused re-engagement may be a signal of a turning point, towards Paris-aligned public clean energy finance by China. It indicates high and increasing potential for China’s clean energy support to fill the energy support gap that was previously provided to fossil fuels.

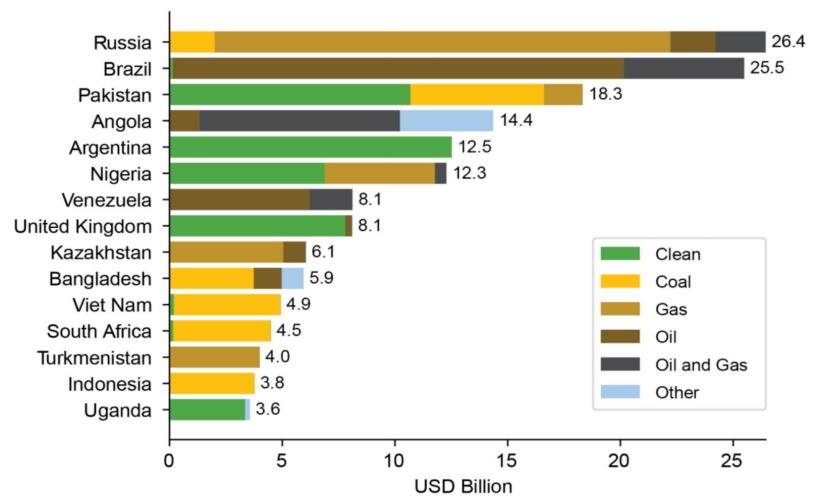

Geographically, while their energy finance span across diverse global regions (see Figure 4), the BRI has been at the center of its landscape. Among the top 15 recipient countries during 2013-2021, a dominant 13 are BRI partner countries (except Brazil and the UK), collectively receiving a significant portion of the energy financing. Notably, clean energy investment was greatly concentrated in several countries (Pakistan, Argentina, the UK, Nigeria and Uganda), with large hydro projects dominating the portfolio, followed by nuclear. CEXIM led in the number of projects financed (44), but CDB topped in total monetary value (USD 100.8 billion).

Figure 4: Geographical distribution of China’s export finance institutions’ energy finance (2013-2021)

Source: Authors, based on OCI (2024)

In recent years, directed by the new investment approach of ’Small and Beautiful’ (小而美), China has been pivoting towards more sustainable and smaller-scale overseas financing (e.g., Ray, 2023; WANG, 2023). The two clean energy projects below provide examples of such support by the three Chinese export finance institutions.

CEXIM and CDB: Hydropower station in Pakistan In 2017, CEXIM and CDB co-financed the construction of the 720 MW Karot Hydropower Plant in Pakistan, along with the China Silk Road Fund. CEXIM led the consortium of financiers in this project, with three financers providing a loan of USD 315 million each (CEXIM, 2024). As of June 2023, the Karot power station has cumulatively generated 3.64 billion kWh of power. This project also receives multilateral support through the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in form of a loan over USD 100 million (Beltroad Initiative, 2018; OCI, 2024). As of June 2023, it is estimated to reduce carbon emissions by 3.98 million metric tons and cover the power needs of the 5 million local people (CDB, 2023; CEXIM, 2024). |

SINOSURE: Solar PV power station project in Saudi Arabia In January 2024, SINOSURE announced to insure an amount of up to USD 220 million for the 2.6 GW solar PV power station project in Saudi Arabia, the largest PV power station project under construction worldwide. After completion, the total power generation is expected to reach 282.2 billion kWh over 35 years, equivalent to saving nearly 245 million tons of CO2 emissions (SINOSURE, 2024b). |

3.4. Progress on governance and policy for clean energy finance

To contribute to China’s climate commitments and ‘Dual Carbon’(双碳) goals, ECAs are already active in translating the 'Philosophy of Green Development' (绿色发展理念), ‘A Global Community of Shared Future’ (人类命运共同体) and 'Xi Jinping Thought on Ecological Civilization' (习近平生态文明思想) into financial practices (CDB, 2024b; CEXIM, 2024; SINOSURE, 2024a). While not explicitly mentioning export finance, the three norms have been adopted to guide China’s overseas investment and financing activities, integrating ’green’ aspects into the process of outbound investment and cooperation (MOFCOM, 2013; State Council, 2023; MFA, 2024).

As early as 2007 – as one of the first banks in China – CDB developed a green credit strategy to encourage green credit business and to proactively manage the environmental and social risks of credit lines. CDB started to publish the Sustainability Report annually in 2018 and signed the Memorandum of Understanding on DFIs’ Principles for Responsible Financing in 2020, promoting green finance and sustainability among BRICS counterparts (CDB, 2021). In 2023, CDB implemented a green and low-carbon finance strategy while refining its green finance management mechanisms. It actively promotes the establishment of a ‘1+N+x+y’ policy system to support carbon peaking and carbon neutrality before 2030 and by 2060 respectively (The State Council, 2021; CDB, 2024a). Meanwhile, CDB has strengthened its Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) risk management by establishing a customer ESG rating system. The bank evaluates customers’ ESG performance and utilizes the results in payment pricing and classification, integrating ESG throughout the credit management process (ibid.).

CEXIM established a special leading group on sustainable development in 2020 which is responsible for coordinating green finance, environmental protection, and ecological civilization related work (CEXIM Shenzhen Branch, n.d.). In 2021, CEXIM identified green and low-carbon transformation as major development goals in its 14th Five-Year Plan (CEXIM, 2022, p. 7). Meanwhile, CEXIM adopted the Green Finance Work Plan (2022-2025) and released its Green Financing Framework, which instructs the bank to evaluate and select green financing transactions, and aims to direct more resources into these areas (CEXIM, 2022, p. 8). In 2023, CEXIM established a Green Finance Committee, and formulated the Principles for the Green Finance Committee. It also revised the Green Credit Guidelines to further enhance its ESG risk management and green credit management throughout the lifecycle of credit businesses (CEXIM, 2024).

SINOSURE witnessed an important year of green finance in 2021, where it established a leading group for promoting green finance, issued the ‘Guiding Opinions on Strengthening Green Finance Construction’, and incorporated green finance and green development transformation into top-level institutional policies such as the 14th Five-Year Plan (CBIMC, 2022). In 2022, SINOSURE formulated the implementation plan of China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission’s (CBIRC) green guidelines, and published projects’ classification and clients’ label policies according to their green level (SINOSURE, 2023). In the same year, SINOSURE integrated the EU–China Common Ground Taxonomy – as a bridge between the EU Taxonomy and China's green finance classification system – into its business decisions for identifying green projects (SINOSURE, 2023).

4. A greener path ahead for China

4.1. Innovative financing instruments

As discussed above, ECAs can wield significant influence on global clean energy financial flows through their diverse financing instruments (see Table 2). Depending on their mandate, ECAs can support exporters with a plethora of instruments, including direct lending to exporters or their customers, and providing credit guarantees or insurance to reduce the cost of financing and attract additional private and public sources of finance. ECAs provide, for example, guarantees to hedge risks against an exporter or lender not being repaid, e.g., due to political instability, expropriation, or unexpected currency fluctuations. Some ECAs also act as direct lenders with short-, medium- or long-term loans and may provide earmarked project finance or even equity instruments. In return, they receive risk premiums or interest payments. In the case of repayment loss, ECAs compensate exporters or lenders directly while being in the position to draw up debt settlement arrangements with the Paris Club. In recent years, global ECAs have expanded their offerings to include more innovative instruments, being proactive in sustainable finance loans. Additionally, ‘greening’ traditional instruments is a common practice, such as offering relaxed underwriting criteria, longer repayment periods, and higher maximum insured amounts for green projects.

Table 2: Overview of ECAs' most important financing instruments

Type |

Instrument |

Chinese ECAs |

Advanced OECD-ECAs |

Traditional instruments |

Official export buyer’s credit (pure cover ECAs) |

R |

R |

Credit insurance and guarantee (pure cover ECAs) |

R |

R |

|

Short-, medium- or long-term loans (multi-purpose ECAs) |

R |

R |

|

Overseas investment (multi-purpose ECAs) |

R |

R |

|

‘Greened’ traditional instruments |

Smaller premium or interest rate, longer repayment periods of loans for green deals and projects (e.g., OECD) |

R |

R |

Green export credit guarantees with relaxed underwriting criteria (e.g., Sweden’s EKN) |

R |

R |

|

Green insurance with higher maximum insured amounts for green deals (e.g., OECD) |

£ |

R |

|

Climate-resilient debt clauses in eligible lending (e.g., UKEF) |

£ |

R |

|

Green cover (e.g. the Dutch Atradius DSB) |

£ |

R |

|

Selected novel green instruments |

Sustainable finance (e.g., Bpifrance’ ‘Bonus Climat’, UKEF’s Clean Growth Direct Lending Facility, and EIFO’s venture capital funds for ‘green’ start-ups) |

R |

R |

Transition finance support for green small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (e.g., UKEF) |

£ |

R |

|

Blended finance to leverage additional resources for climate-related investment |

£ |

R |

|

Risk-sharing arrangements for large-scale green projects |

£ |

R |

Source: Authors, based on E3F (2024), Perspectives Climate Research (2024) and Schmidt et al. (2024).

Note: For the comparisons above, we have assessed ECAs of twelve OECD countries between 2021 and 2024, including Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, South Korea, Sweden, United Kingdom and United States.

While China has embraced some ‘greened’ instruments, a gap exists in the implementation of more innovative green financing tools. The absence of certain novel green instruments in Chinese export finance institutions' toolkit indicates potential areas for future development. As global pressure but also opportunities for green finance increase, Chinese ECAs need to develop their green offerings further, possibly with ‘Chinese characteristics’, to maintain competitiveness in the global market while aligning with China's climate commitment and green finance ambition.

4.2. Advancing green finance leadership

As the world's manufacturing hub of solar panels, wind turbines, lithium-ion batteries and EVs (IEA, 2024), China’s export finance institutions can leverage the expertise of the country’s clean energy sector to strengthen its position as the leader of clean energy solutions to the world, accelerating RE deployment and investment globally. By further diversifying its investment beyond the ‘New Three’ to novel climate technologies, China can build more comprehensive green project pipelines. This should include climate-resilient RE such as China-patented wind turbines that can harness energy even during the strongest hurricanes (e.g., China News, 2024; Sankaran, 2024), which could be particularly beneficial for many Small Island Development States (SIDS) such as in the Caribbean and the Pacific but also for the US East Coast, for instance.

Furthermore, following previous efforts by the Chinese government, the three institutions are well-positioned to lead on energy transition. As early as 2015, China established the South-South Climate Cooperation Fund to support the Global South in green transitions, including trade and investment facilitation (BRI, 2018; South-South Cooperation Fund, n.d.). In 2023, the Green Investment and Finance Partnership (GIFP) was announced to help BRI partner countries develop green projects (Gallagher et al., 2023). During the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in September 2024, even more positive signals on green cooperation were released. President Xi stated that China will help develop 30 specific clean energy projects and encourage more investments in utilizing RE across Africa (Patel, 2024). In an action plan for 2025-2027, green development was recognized as one of the ten partnership initiatives between China and Africa, suggesting greener cooperation (FOCAC, 2024). Most recently at COP29, China announced to have already provided and mobilized climate finance of more than USD 24.5 billion for developing countries since 2016 (Hou, 2024), making the country the joint fifth-largest climate finance provider after Japan, Germany, the US and France (Lin, 2024). According to COP29 president Mukhtar Babayev, “China would have offered more money to the poor world to tackle the climate crisis” if negotiations for a new climate finance goal would not have ended at USD 300 billion by 2035 (Carbon Brief, 2024). These developments demonstrate China’s leadership and commitment in South-South climate cooperation.

5. Conclusion

ECAs have a pivotal role to play in the global push to phase out fossil fuels. Despite their ongoing large support for carbon-intensive projects, recent commitments show a growing momentum towards clean energy finance. By leveraging innovative and ‘greening’ existing financing instruments, ECAs can help build green project pipelines and facilitate clean technology exports. However, systematic reforms are needed to level the export finance playing field globally, to close loopholes for continued fossil fuel support, and ensure that all ECAs support rather than stall energy transitions.

As the world’s largest emerging economy, China has made remarkable progress in transitioning towards clean energy finance domestically. Internationally, as the world’s manufacturing hub for the ‘New Three’ exports, China's export finance institutions are well-positioned to increasingly provide large-scale clean energy solutions and promote capacity building in countries of the Global South such as its co-members of the G77, aligning with the country’s climate commitments and leadership ambition.

By further accelerating green export finance, CDB, CEXIM and SINOSURE can reduce exposure to climate-related risks associated with fossil fuel investments, drive innovation in domestic green industries, and unlock potential opportunities for higher returns on clean investments. This would enhance their global competitiveness and open access to the burgeoning markets for sustainable products and services. ECAs’ green practices can also set a precedent for other emerging economies such as China’s partners in the G77 to follow suit, catalyzing their ECAs to play a more proactive role in energy transitions.

References

AidData (2023) AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0. Available at: https://www.aiddata.org/data/aiddatas-global-chinese-development-finance-dataset-version-3-0 (Accessed: 27 July 2024).

Beltroad Initiative (2018) BRI Factsheet Series - Karot Hydropower Plant - Belt and Road Initiative, Belt and Road Initiative -, 12 August. Available at: https://www.beltroad-initiative.com/bri-factsheet-series-karot-hydropower-plant/ (Accessed: 7 September 2024).

Berne Union (n.d.) Berne Union Climate Working Group. Available at: https://www.berneunion.org/Stub/Display/234 (Accessed: 17 April 2024).

BRI (2018) 中国气候变化南南基金. Available at: https://obor.nea.gov.cn/v_finance/toFinancialDetails.html?countryId=215&status=2 (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

Carbon Brief (2024) China was willing to offer more in climate finance, says COP29 president - Carbon Brief. Available at: https://www.carbonbrief.org/daily-brief/china-was-willing-to-offer-more-in-climate-finance-says-cop29-president/ (Accessed: 26 November 2024).

CBIMC (2022) 中国信保绿色项目保额约77亿美元_中国银行保险报网, 20 April. Available at: http://www.cbimc.cn/content/2022-04/20/content_460111.html (Accessed: 27 July 2024).

CCPITGS (2013) 出口信用保险的现状. Available at: https://www.ccpitgs.com/channels/mycj/ckxybx/4514-0607160500.html (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

CDB (2021) CDB Annual Report 2020. Beijing: CDB. Available at: https://www.cdb.com.cn/gykh/ndbg_jx/2020_jx/ (Accessed: 19 August 2024).

CDB (2023) 国家开发银行:发挥开发性金融融资引领作用服务共建“一带一路”行稳致远. Available at: https://www.cdb.com.cn/xwzx/khdt/202310/t20231012_11161.html (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

CDB (2024a) CDB Sustainability Report 2023. Beijing: CDB. Available at: https://www.cdb.com.cn/bgxz/kcxfzbg1/kcx2023/ (Accessed: 29 August 2024).

CDB (2024b) China Development Bank Annual Report 2023. Beijing: CDB. Available at: https://www.cdb.com.cn/English/gykh_512/ndbg_jx/2023_jx/ (Accessed: 9 July 2024).

CDB (n.d.) About China Development Bank. Available at: https://www.cdb.com.cn/English/gykh_512/khjj/ (Accessed: 27 July 2024).

CEXIM (2022) Green financing framework. Available at: http://www.eximbank.gov.cn/info/ztzl/lsxdzdhz/202302/P020230201390185031891.pdf (Accessed: 8 August 2024).

CEXIM (2024) Annual Report 2023. CEXIM. Available at: http://www.eximbank.gov.cn/aboutExim/annals/2023/202404/P020240429537409675431.pdf (Accessed: 20 May 2024).

CEXIM (n.d. a) Business. Available at: http://english.eximbank.gov.cn/Business/ (Accessed: 27 July 2024).

CEXIM (n.d. b) Credit Ratings. Available at: http://english.eximbank.gov.cn/Profile/AboutTB/CreditR/201807/t20180716_5941.html (Accessed: 27 July 2024).

CEXIM Shenzhen Branch (n.d.) Environmental Information Disclosure Report 2022. Shenzhen: CEXIM Shenzhen Branch. Available at: http://www.eximbank.gov.cn/info/WhitePOGF/202308/P020230821614812451049.pdf (Accessed: 20 August 2024).

Chen, Han and Wei Shen (2022) China’s no new coal power overseas pledge, one year on, Dialogue Earth, 22 September. Available at: https://dialogue.earth/en/energy/chinas-no-new-coal-power-overseas-pledge-one-year-on/ (Accessed: 8 August 2024).

Chen, Muyang (2020) Beyond Donation: China’s Policy Banks and the Reshaping of Development Finance, Studies in Comparative International Development, 55(4), pp. 436–459. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-020-09310-9.

Chen, Yunnan and Zongyuan Liu (2023) Hedging belts, de-risking roads: Sinosure in China’s overseas finance and the evolving international response. London: ODI. Available at: https://odi.org/en/publications/hedging-belts-de-risking-roads-sinosure-in-chinas-overseas-finance-and-the-evolving-international-response/ (Accessed: 18 April 2024).

China News (2024) 中国造全球最大漂浮式风机、最大海上风机成功抵御超强台风. Available at: https://m.chinanews.com/wap/detail/chs/zw/10282394.shtml (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

Christophers, Brett (2024) We must not mistake China’s success on green energy for..., Financial Times, 20 July. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/3043fca2-111c-441f-985b-557aa2efa3a0 (Accessed: 29 August 2024).

Club de Paris (2021) Definition of debt treated. Available at: https://clubdeparis.org/en/communications/page/definition-of-debt-treated (Accessed: 28 April 2024).

DeAngelis, Kate and Bronwen Tucker (2021) Past Last Call - G20 public finance institutions are still bankrolling fossil fuels. Washington DC,: OCI and Friends of the Earth US. Available at: https://priceofoil.org/content/uploads/2021/10/Past-Last-Call-G20-Public-Finance-Report.pdf (Accessed: 18 April 2024).

E3F (2022) Export Finance for Future (E3F) Transparency Reporting. Available at: https://www.ekn.se/globalassets/dokument/hallbarhetsdokument/e3f-transparency-report-2022.pdf (Accessed: 20 April 2024).

E3F (2023) E3F Status Report 2023. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/export-finance-for-future-e3f_e3f-status-report-2023-activity-7136818051324227584-w0Bb/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop (Accessed: 6 June 2024).

E3F (2024) E3F Additional Climate Positive Products. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/export-finance-for-future-e3f_e3f-additional-climate-positive-products-activity-7261716356666970112-fHJ2/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

Engel, Lucas, Jyhjong Hwang, Diego Morro and Victoria Yvonne Bien-Aime (2024) Relative Risk and the Rate of Return. Boston: Boston University. Available at: https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2024/08/GCI-PB-23-CLA-2024-FIN.pdf (Accessed: 16 September 2024).

European Commission (2023) OECD members agree to EU initiative to modernise export credits, 3 April. Available at: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/news/oecd-members-agree-eu-initiative-modernise-export-credits-2023-04-03_en#:~:text=The%20maximum%20repayment%20term%20will,years%20for%20most%20other%20projects. (Accessed: 5 April 2024).

FOCAC (2024) Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan (2025-2027). Available at: http://www.focac.org/eng/zywx_1/zywj/202409/t20240926_11497783.htm (Accessed: 27 September 2024).

Gallagher, Kevin, Rebecca Ray and Oyintarelado Mose (2023) Experts React: The Belt and Road Ahead, 27 October. Available at: https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2023/10/27/experts-react-the-belt-and-road-ahead/ (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

Hale, Thomas, Andreas Klasen, Norman Ebner, Bianca Krämer and Anastasia Kantzelis (2021) Towards Net Zero export credit: current approaches and next steps. Available at: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/publications/towards-net-zero-export-credit-current-approaches-and-next-steps (Accessed: 28 May 2024).

Hou, Liqiang (2024) China praised for climate financial aid - Chinadaily.com.cn, 18 November. Available at: //epaper.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202411/18/WS673a8ea7a3105c25b38edcba.html (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

IEA (2024) Renewables 2024: Analysis and forecast to 2030. Paris: IEA. Available at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/88a07dd9-42fe-4232-842e-9015b4b647f8/Renewables2024.pdf (Accessed: 3 October 2024).

IPSF (2022) Common Ground Taxonomy - Climate Change Mitigation. Hague: International Platform on Sustainable Finance. Available at: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-06/220603-international-platform-sustainable-finance-common-ground-taxonomy-instruction-report_en.pdf (Accessed: 8 August 2024).

Jones, Natalie (2024) Leaders are cutting fossil fuel finance – next comes unlocking clean energy for all, Climate Home News. Available at: https://www.climatechangenews.com/2024/08/29/leaders-are-cutting-fossil-fuel-finance-next-comes-unlocking-clean-energy-for-all/ (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

Jones, Natalie and Bokyong Mun (2023) Putting Promises Into Practice: Clean Energy Transition Partnership signatories’ progress on implementing clean energy commitments. IISD. Available at: https://www.iisd.org/publications/report/putting-promises-into-practice-cetp-commitments (Accessed: 28 March 2024).

Jones, Natalie, Claire O’Manique, Adam McGibbon and Kate DeAngelis (2024) Out With the Old, Slow With the New. Winnipeg: IISD. Available at: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2024-08/countries-underdelivering-fossil-clean-energy-finance-pledge.pdf.

King, Beatrice, Igor Shishlov, Axel Michaelowa Axel, Max Schmidt and Olivia Walls (2023) Renewable Energy Investments in Times of Geopolitical Crisis. The Al-Attiyah Foundation. Available at: https://www.abhafoundation.org/media-uploads/reports/Sustainability-04-2023-April-Print.pdf (Accessed: 16 August 2024).

Klasen, Andreas, Simone Krummaker, Julia Beck and James Pennington (2024) Navigating geopolitical and trade megatrends: Public export finance in a world of change, Global Policy, 00, pp. 1–8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13417.

Klasen, Andreas, Roseline Wanjiru, Jenni Henderson and Josh Philipps (2022) Export finance and the green transition, Global Policy, 13(4). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13121.

Lin, Zi (2024) Will China assume more responsibility for global climate finance?, Dialogue Earth, 19 November. Available at: https://dialogue.earth/en/climate/will-china-assume-more-responsibility-for-global-climate-finance/ (Accessed: 26 November 2024).

Ma, Xinyue and Kevin P. Gallagher (2021) Who Funds Overseas Coal Plants? The Need for Transparency and Accountability. Boston: Global Development Policy Center. Available at: https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2021/07/07/who-funds-overseas-coal-plants-the-need-for-transparency-and-accountability/ (Accessed: 20 April 2024).

MFA (2024) List of Deliverables for a Shared Future Actions Plan (50 items)_Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Available at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zy/jj/GDI_140002/wj/202408/t20240802_11465339.html (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

MOFCOM (2013) Notification of the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Environmental Protection on Issuing the Guidelines for Environmental Protection in Foreign Investment and Cooperation -. Available at: http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/policyrelease/bbb/201303/20130300043226.shtml (Accessed: 27 July 2024).

OCI (2024) Dashboard - Public Finance for Energy Database. Available at: https://energyfinance.org/#/data (Accessed: 17 July 2024).

OECD (2021) Export credits. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/export-credits.html (Accessed: 28 April 2024).

OECD (2024) Bridging the clean energy investment gap. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2024/07/bridging-the-clean-energy-investment-gap_a524f35e.html (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

O’Manique, Claire, Bronwen Tucker and Kate DeAngelis (2024) Public enemies: Assessing MDB and G20 international finance institutions’ energy finance. Washington D.C.: OCI. Available at: https://priceofoil.org/content/uploads/2024/04/G20-Public-Enemies-April-2024.pdf (Accessed: 30 August 2024).

Patel, Anika (2024) In-depth: China’s finance for African renewables rebounds after two-year lull, Carbon Brief. Available at: https://www.carbonbrief.org/in-depth-chinas-finance-for-african-renewables-rebounds-after-two-year-lull/ (Accessed: 21 September 2024).

Perspectives Climate Research (2024) Export Credit Agencies. Available at: https://perspectives.cc/initiative/eca/ (Accessed: 6 April 2024).

Ray, Rebecca (2023) “Small is Beautiful”: A New Era in China’s Overseas Development Finance? Boston: Boston University. Available at: https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2023/01/GCI_PB_017_CODF_EN_FIN.pdf (Accessed: 20 August 2024).

Rudyak, Marina (2020) Who is Who in the Chinese Lending Institutional Landscape. urgewald. Available at: https://www.urgewald.org/en/shop/who-who-chinese-lending-institutional-landscape (Accessed: 27 May 2024).

Sankaran, Vishwam (2024) China plans to harness energy from hurricanes using giant turbines, The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/tech/china-hurricane-energy-giant-turbines-b2581740.html (Accessed: 27 July 2024).

Schmidt, Max, Philipp Censkowsky, Ziqun Jia and Igor Shishlov (2024) Paris Alignment of Export Credit Agencies - Case Study #9: Sweden (EKN & SEK). Freiburg: Perspectives Climate Research. Available at: https://pub.norden.org/temanord2024-536/temanord2024-536.pdf (Accessed: 31 July 2024).

Schmidt, Max, Ziqun Jia and Igor Shishlov (2024) Accelerating Renewable Energy Investments to Meet COP28 Goals by 2030. The Al-Attiyah Foundation. Available at: https://www.abhafoundation.org/media-uploads/reports/SD-05-2024-May-Email.pdf (Accessed: 20 August 2024).

Schmidt, Max, Ziqun Jia, Luisa Weber and Igor Shishlov (2024) Paris Alignment of Export Credit Agencies - Case Study #10: Finland (Finnvera). Freiburg: Perspectives Climate Research.

Schmidt, Max, Igor Shishlov, Philipp Censkowsky, Ziqun Jia and Luisa Weber (2024) Best Practice Guide for the Paris Alignment of Export Credit Agencies. Freiburg: Perspectives Climate Research.

SINOSURE (2023) SINOSURE Annual Report 2022. Beijing: SINOSURE. Available at: https://www.sinosure.com.cn/images/xwzx/ndbd/2023/07/03/7E85B5D6FEB489239452F18F02EE3F08.pdf (Accessed: 7 August 2024).

SINOSURE (2024a) SINOSURE Annual Report 2023. Beijing: SINOSURE. Available at: https://www.sinosure.com.cn/images/xwzx/ndbd/2024/07/09/961D4764432B71CF10660C000F29D9F9.pdf (Accessed: 12 July 2024).

SINOSURE (2024b) 中国信保承保全球最大在建光伏电站项目. Available at: https://www.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/091CL0GO.html (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

SINOSURE (n.d.) Company profile. Available at: https://www.sinosure.com.cn/en/Sinosure/Profile/index.shtml (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

Song, Wanyuan, Verner Viisainen and Anika Patel (2024) Q&A: The global ‘trade war’ over China’s booming EV industry, Carbon Brief, 28 August. Available at: https://www.carbonbrief.org/qa-the-global-trade-war-over-chinas-booming-ev-industry/ (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

South-South Cooperation Fund (n.d.) South-south cooperation fund. Available at: http://en.cidca.gov.cn/southsouthcooperationfund.html (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

Springer, Cecilia, Ishana Ratan, Yudong Liu and Jia Gu (2023) Green Horizons? China’s Global Energy Finance in 2022 | Global Development Policy Center, 13 November. Available at: https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2023/11/13/green-horizons-chinas-global-energy-finance-in-2022/ (Accessed: 27 September 2024).

State Council (2023) 共建“一带一路”:构建人类命运共同体的重大实践_白皮书_中国政府网. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202310/content_6907994.htm (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

The State Council (2021) 国务院印发《2030年前碳达峰行动方案》, 26 October. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-10/26/content_5645001.htm (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

TXF (2023) Export finance H1 2023: A rising tide lifts all boats, TXF, 18 August. Available at: https://www.txfnews.com/articles/7582/export-finance-h1-2023-a-rising-tide-lifts-all-boats (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

UNFCCC (2023) First Global Stocktake Proposal by the President. UNFCCC. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2023_L17_adv.pdf (Accessed: 1 October 2024).

UNFCCC (n.d.) Contributing Parties. Available at: https://unfccc.int/climatefinance/fsf/donors (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

WANG, Christoph NEDOPIL (2023) Ten years of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Evolution and the road ahead. Shanghai: Green Finance & Development Center. Available at: https://greenfdc.org/ten-years-of-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-bri-evolution-and-the-road-ahead/ (Accessed: 27 July 2024).

Weber, Luisa, Max Schmidt and Igor Shishlov (2024) Paris Alignment of Export Credit Agencies: Denmark. Freiburg: Perspectives Climate Research.

Zhang, Jing and Christoph Nedopil (2024) China Green Trade Report 2023. Brisbane: Griffith University. Available at: https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0032/1952249/Zhang_Nedopil_China-green-trade_2023-Report.pdf (Accessed: 8 August 2024).